Intro

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gG6WnMb9Fho

We have constantly read about the need to develop certain skills beyond hard skills. Several authors and organizations put the emphasis on the rapidly changing characteristics of our world on all its manifestations: ecological, economic, social, educational, labor and, now particularly, on health. Something very important about these skills / competencies is that they are “portable”, that is, just as hard skills are usually specific to the sector in which you will work, soft skills can be used in almost any context or sector and even they can help you move from one sector to another and that is where their vital importance lies in a context as uncertain and volatile as the one we live in.

For example, at the beginning of 2020 the famous Israeli historian and writer Yuval Harari was invited to the Davos forum to give a talk entitled “How to Survive the 21st Century”, in this same conference he indicated that to survive as workers we will need to have the ability to learn new skills fast enough. The change in sectors and jobs would be a constant cascade of “disruptions” due to the automation revolution and, therefore, it would be necessary that in each situation we could reinvent ourselves several times throughout our, more and more complicated, working life. The current approach to the development of AI (Artificial Intelligence) will produce unprecedented new levels of inequality, even between countries. According to Harari, if we are not able to develop certain skills, it is very likely that at work we will become part of the “Useless class”, which we have seen so much in countless cyberpunk science fictions but which, unfortunately, threatens to become a very close reality.

Without going into details about the suitability of said mutability in our day to everyday life, the truth is that those same organizations and researchers, mentioned at the beginning, constantly preach about the need to train and identify soft skills, also called transversal competences, survival skills or skills for life and this is precisely one of the reasons why I decided to write this article, because there is no standard system of skills, at least one similar to the current system of hard skills or competencies.

In this article I intend to list the existing classifications, the different ways of naming what in media slang we have come to know as Soft Skills but which, in other taxonomies, can even be referred to as “attitudes” and even “values”.

A definition for Soft Skills?

In the first place, the “catalog of soft skills varies a lot from one study or intervention to another and includes a wide range of attributes”, This is the comment of the research team led by Chamorro in 2015 with the title Soft skills in higher education. As we will see later, this is the main problem with Skills today, not only does their importance vary in terms of which are more relevant depending on the time we live in, but depending on the organization , group or even nation, these are going to be named and defined in non-standard ways. Names, descriptors and even indicators are completely different over time and the organization that states them.

The issues related to the definition and training in key soft skills or transversal skills are not new, in 1996 Sonia Blisset and Robert McGrath in an investigation on the relationship between skills Creativity and Problem Solving indicates that these are complementary skills to each other and that the related literature was almost always related to therapeutic contexts. In the case of Creativity, they mention incipient works from the 60s, 70s and 80s where this skill is linked to Problem Solving. Both authors carry out an experiment with 74 university students, so it seems obvious that these skills have been chosen by them in the experiment as a reflection of the need to academically implement the training of mentioned skills within a formal education framework.

The issues related to the definition and training in key soft skills or transversal skills are not new, in 1996 Sonia Blisset and Robert McGrath in an investigation on the relationship between skills (skills in the original in English) Creativity and Problem Solving indicates that these are complementary skills to each other and that the literature on training in these was almost always related to therapeutic contexts. In the case of Creativity, he mentions incipient works from the 60s, 70s and 80s where he connects this competence with that of Problem Solving. Both authors carry out an experiment with 74 university students, so it seems obvious that these skills have been chosen by them in the experiment as a reflection of the need to academically implement their training in a formal education framework.

Cukier et al. review different descriptions in their Soft Skills are Hard. A 2015 Review of the Literature: Perrault (2004) defines soft skills as “personal qualities, attributes or the level of commitment of a person that distinguishes them from other people who may have similar education and experience”; James and James (2004) “Soft skills are a new way of describing a set of skills or talents that a person can bring to the workplace, including professional attributes such as team skills, communication skills, leadership skills, customer service management skills and problem solving skills “; finally it is explained that “in the Canadian context, soft skills are generally understood to include writing skills, oral communication skills, presentation skills, interpersonal skills, priority and goal setting, and learning skills throughout life” (Canadian Chamber of Commerce, 2014). The text emphasizes some key soft skills, such as leadership skills, critical thinking, problem solving, information management skills and entrepreneurship. This paper also highlights the fact that unfortunately there is very little consensus for a list of soft skills, even in their nomenclature. It is also noteworthy that, in many cases, we do not find the term soft skills but the mention of generic and professional skills.

We deduce from all these descriptions by different authors that soft skills are all non-technical skills / competencies, that is, those that do not come from practical execution as a result of the knowledge acquired through formal / non-formal education and that have an important role in our job or when starting a personal or collective company as entrepreneur. We talk about skills and abilities that make the difference between profiles with similar levels of hard / technical skills. Of course, there is a whole list of these skills to be typified; for example, we would have soft skills related to our own physical, mental or emotional capacities and, on the other hand, we would have those related to our social / communication capacities. These competences act transversally to the specific technical knowledge learned during our formal education.

Getting back to the example of Yuval Harari’s talk about a truck driver: this person has learned a series of hard skills based on technical knowledge about driving heavy vehicles, things that he/she is not able to learn innately or that involve a high cost in terms of self-learning. This technical knowledge is connected with soft skills such as: Cognitive Flexibility, to help him/her to identifying unexpected driving situations that could be potentially dangerous and about which he/she did not receive specific training; Spatial Relationships, which will help he/she to feeling the volume of the vehicle and handling it even when there are space restrictions; o Time Management, to know when to stopping and when to continuing driving to maximize his/her productivity and avoiding fatigue. What do international organizations in education and economics think about these soft skills?

International Organizations and Soft Skills

OECD

The OECD in its 2017 Skills for Job Indicators report already indicates that “growth in employment has been stronger in those jobs where cognitive skills and soft skills were required”, some of which are defined as “Leadership and Adaptability” in the same paragraph. In fact, it stands out that there is a shortage of these skills, especially the shortage is greater in countries where there is a lower proportion of jobs in mechanical or routine jobs, thus producing a significant gap between workforce and job positions (p.9, 19). Later in the report we even find statements like this: “According to the literature on labor market polarization, the results suggest that abstract and soft skills are more in demand than routine skills, and this gap has increased in recent years.” (p. 49), we find similar ideas shared by other researchers such as Cinque (2015) or Cimatti (2016, p. 112).

For the OECD, each individual as a future employee or entrepreneur needs to develop not only a set of “technical skills”, for success in his/her workplace or projects certain soft and social skills must be developed, in part because these skills – unlike the techniques – cannot be automated (yet). Finally, it affects the fact that such soft skills are required in all jobs, although the demand may “differ significantly depending on the sector / position” (p. 78). The list of soft skills now continues with a graph of shortage / demand for them by country: Adaptability (shortage in Ireland, Estonia and Finland), Attention to Detail (Finland, Luxembourg and Austria), Leadership (Ireland, Iceland and the Netherlands ), Persistence (Finland, Luxembourg and Spain). This report concludes on these soft skills:

“Employment in occupations consisting of tasks that are complementary to automation, and often require non-automatable soft skills, has been on the rise […] finding particularly strong growth in jobs combining cognitive and soft skills” (p. 80, 82).

In other words, three years before the Harari conference, the OECD had already detected the trend changes in the labor market, placing emphasis on the training / learning of soft skills as keys to the world of work.

World Economic Forum

A year after Harari’s talk and in the same Davos Forum (also known as the World Economic Forum) a report called Building a Common Language for Skills at Work (2021) was published indicating that 50% of employees worldwide will need a “reskilling” by 2025 and that 40% of the “skills cores” of these same employees will change in the next 5 years. WEF experts define Competences as “Collection of skills, knowledge, attitudes and abilities that allow a person to perform job functions”. Within these Competencies we find Skills and Knowledge, Attitudes and Abilities, all under the protection of what they call Competencies.

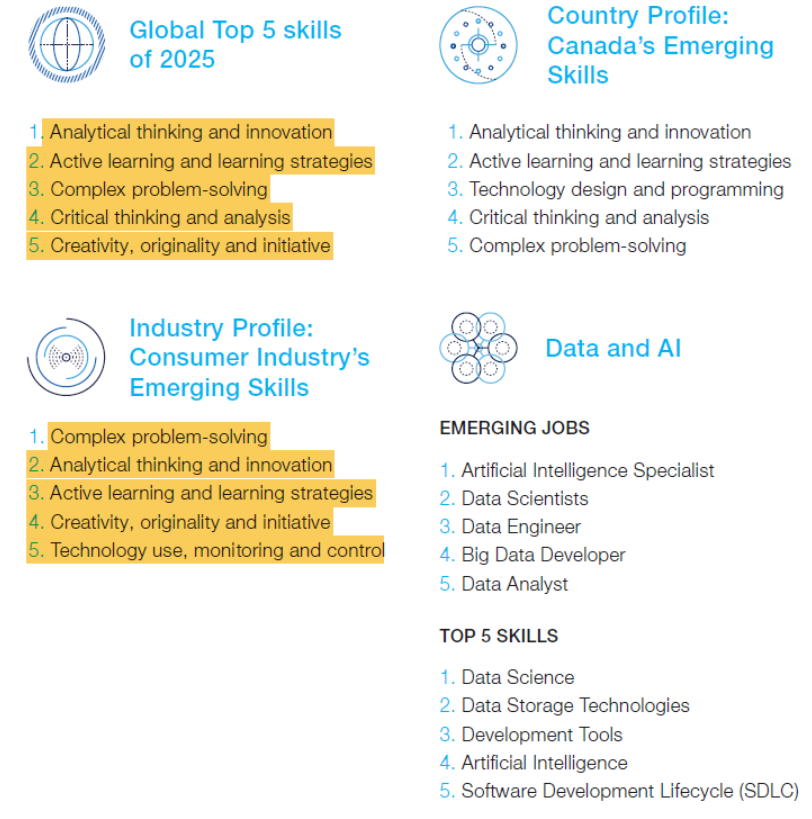

This report generates some confusion, because when the most key “skills” are analyzed according to the different sectors / profiles, all these Competencies end up being called Skills. For example, in the Consumer Industry sector, the following skills are indicated as necessary: Complex Problem-Solving, Analytical Thinking and Innovation, Active Learning, Creativity and Technology Use; just to mention a few. In other words, based on the WEF’s own definition of Skills, Attitudes and Abilities, we could say that Active Learning is more of an Attitude than a Skill itself. More confusion is caused when the key Skills for Data and AI positions are stated, mentioning Data Science and Development Tools that, in fact, are closer to what the document itself defines as Knowledge than as Skill itself. I have to say that this WEF approach to generating a global taxonomy is, to say the least, superficial and confusing and, therefore, not very operational in terms of setting up a standardization that allows us to define a soft skill and, even less, to certify it.

The European models

ESCO

In Europe we have a classification of skills / competences, qualifications and occupations (ESCO for its acronym in English), dependent on the European Commission. In the ESCO model, the Competencies are divided into four, in a very similar way to how the WEF mentioned above does: Attitudes and Values (A), Knowledge (K), Linguistic Competences and Knowledge of Languages (L) and Skills (S). Of all these elements, only the specific definition of one of them is exposed: Attitudes and Values, which are “Individual work styles, preferences and work-related beliefs that underpin behaviour so that knowledge and skills are applied effectively”.

We would also have liked a description for the Skills. We can presume that the Skills in the ESCO model are neither more nor less than the ability we have to use our technical-academic knowledge in an executive way, that is, if we have an S7.3 Skills (install interior or exterior infrastructure) it is because we have surely received a training on (K) Knowledge in civil engineering or construction. However, this does not connect very well with Skills of type S1 (communication, collaboration and creativity), which are not related to any of the branches of Knowledge, with the exception perhaps of the Arts and Humanities but it is understood that these Skills must be developed in and for other sectors, not only in and for the Arts and Humanities one.

Thus, according to the ESCO model we have Attitudes and Values (A) such as Adapting to Change, Paying Attention to Detail, Controlling Frustration or Persevering, not related to any Knowledge (K) or training but it almost seems to indicate that they come like standard within each one of us. However, Skills (S) such as Creativity, Problem Solving, Negotiation or Management Capabilities are also mentioned that are not related to specific Knowledge (K) and that seem to be related to and even being part of Attitudes and Values ( A) such as Showing Curiosity, Showing Enthusiasm, Managing Quality, or Coping with Uncertainty. ESCO, in this way, does not divide Skills (S) between hard (related to Knowledge) and techniques acquired in formal / non-formal education), and soft (the personal traits that allow us a productive performance of the hard Skills in any context / circumstance).

ENTRECOMP

Another framework related to competences and work is the EntreComp framework, which treats entrepreneurship (not only at an economic level, but also culturally and socially) as an essential competence to be developed in the European context. This framework attempts to “build bridges between the worlds of work and education.”

In this framework, the Entrepreneurship competence (or meta-competence) is in turn splitted into other competencies that are part of three families or areas: Ideas-Opportunities, Resources and Actions. Somehow it seems like a division between mental, emotional, social and executive competencies.

To put some examples (see chart above):

- Ideas and Opportunities we find:

- Creativity

- Vision

- Ideas Evaluation

- Among the Resources:

- Motivation and perseverance

- Mobilization of Others

- Resource Mobilization

- Into Action:

- Take the initiative

- Plan and Manage

- Work with Others.

In addition, this framework has different levels of Proficiency: Basic, Intermediate and Advanced, each one of them, with very precise descriptors of each of these levels that, in addition, are divided into two scales each.

The EntreComp framework is a good example of Competences analysis that, in many ways, we could call “soft”. The methodology of the EntreComp framework is very interesting from the fact that it uses this figure of entrepreneur to make an a posteriori analysis of the Competences (divided into families), although for them Competencies includes both Knowledge, Skills and Attitudes. The diagram on page 11 of the report is very revealing, since Attitudes and Skills are almost exclusively included here, however Skills are defined according to the 2008 European framework (p. 21), thus inheriting the deficiencies of that framework, in our humble opinion, still premature.

Soft Skills and Education

What can we say about Formal Education?

‘Over eight in 10 teachers (83%), parents (82%), superintendents (82%), and principals (83%) say it is equally important to assess both academic skills and nonacademic skills such as teamwork, critical thinking, and creativity (….), although only about one in 10 teachers say that the formal and informal assessments used by their schools to gauge nonacademic skills measure them “very well’. These are the hard results of a joint work between NWEA (Northwest Evaluation Association) and the Gallup consultancy in 2018 (p. 2).

In 2017 PDK Poll had already revealed that American citizens wanted colleges to focus more on areas other than exclusively academic ones. 82% of respondents indicated that it is very important that schools help students develop interpersonal skills such as knowing how to cooperate, be respectful with others and persistent in solving problems. The survey also found that 82% support job and career skills classes, even if that means students should spend less time in academic classes (p. 3).

However, and although it seems that at a teaching and family level there is a clear awareness of the need to train these skills in some way, the outlook is quite bleak even in the US, not only in the matter of measuring these skills, which, in most cases are “trained by themselves”, that is, informally and without control, but the curriculum design itself does not include them. In this sense, one of the main directors who participated in the research commented that “We don’t have the time that we need to

reach out to the kids that are struggling the most with the nonacademic skills”, and several teachers recommended a change in the curriculum focused on learning based on projects as a way to develop critical thinking and problem solving skills (p. 8).

Another famous North American researcher and teacher, Tony Wagner, also highlighted the shortcomings of the formal educational system regarding certain competencies in his book The Global Achievement Gap (2008). In it he lists a series of competencies, called “survival skills” that should be present in the curricular programs of schools and high schools in the United States:

- Critical Thinking and Problem Solving

- Collaboration through Networks and Leadership by Influence

- Agility and Adaptability

- Initiative and Entrepreneurship

- Effective Oral and Written Communication

- Information Access and Analysis Capacity

- Curiosity and Imagination.

That is to say, for Tony Wagner, these competencies are so key that it even indicates that the survival of the economy and the work of his country would be threatened if a change is not carried out at the pedagogical level that includes these ‘survival skills’ within schools and institutes curricula. Some of these competencies can be, to some extent, easily trainable, as is the case of Effective Oral and Written Communication. In other cases there is a close relationship with Digital Competences, as it happens when he talks about Access Capacity and Information Analysis. For the rest of the competences, such as Agility, Leadership, Problem Solving, Adaptability, etc., there is no specific curricular design, there is hardly a definition, much less a formal or informal training and evaluation system. A statement in this regard helps us to ground the current situation: “The exceptions to the rule – teachers who use academic content as a way to teach their students how to communicate, reason and solve problems – are very rare, less than one for each twenty in our experience. His lessons stand out in stark contrast to what is usually seen in most classes. ” (p.65)

Discussion

From our point of view there are several attempts, especially since the 1990s, to narrow down, define and relate certain “skills” or “competencies” outside the framework of hard skills. These attempts have gained special relevance since some international organizations and research teams have linked the development of a new economic and industrial context with the demand for qualified workers but also holders of additional values in the form of Attitudes and Competencies, beyond their Hard Skills and Technical Competences resulting from knowledge acquired from formal and non-formal education. These Non-Technical Competences appear mixed in the different standardization attempts depending on the different organizations that have taken the initiative to standardize their names and descriptors. In many cases, it is difficult to differentiate when it is a psychological attitude towards a task and when it is a competence based on abilities and skills, for example, in the management of an individual or collective context that can positively or negatively influence the success of said task.

One of the frameworks that best defines the relationship between a social / labor / economic profile and “other competences”, that is, non-hard competencies, is the EntreComp framework of the IPTS-JRC of the European Commission. Starting from the premise about what capacities / training should an entrepreneurial profile have got (such as social, cultural entrepreneur, etc., not only economic one), a meticulous investigation has been carried out thanks to a complex work methodology that puts in the center this figure (entrepreneur) and the necessary competencies to promote said profile (Competences: Ideas and Opportunities, Resources and Actions). In addition, this frame of reference is divided into levels of acquisition and development of every competence, these levels are explained in a very meticulous way and these rubrics could be transferred to another new list of competencies based on new profiles investigated through this methodology.

Another concern we find when analyzing soft skills is their evaluation. It is true that in all the previous cases there are conversations about the need to promoting these Competencies so that future workers will have them, however their evaluation is extremely complicated: “many of these attributes can only be assessed subjectively, that is there are no objective tests for, say, interpersonal and management skills. Moreover, several of the attributes that constitute soft skills taxonomies refer to dispositional traits that may change very little during the years of higher education and are known to affect academic grades” (Chamorro-Premuzic et al, 2010). Perhaps this is one of the reasons why formal and non-formal education find it more difficult to include training programs in soft skills in their curricular designs. In the first place, because it does not exit a list of specific competences with clear descriptors (rubrics) to train them; on the other hand, there is the fact that these skills also change depending on the need of each training / work cycle and, finally, because the forms of measuring these (in many cases standard tests) are subjective or clearly out of date since many of these more “recent” tests are from the late twentieth century.

In our opinion and as a summary, everything indicates that there is still a lot of work to be done in order to be able to define all this compendium that are the “not hard” competences, to clearly separate Attributes, Attitudes and Soft Competences, to define and to describe them. Once this work of, at least, semi-standardization has been completed, the evaluation methods should be reviewed, including new rubrics and also new measurement systems that are not just paper and pen tests (whether analog or digital) and also including experiential methodologies of training and assessment (whether analog or digital) and finally to start implementing these in formal and non-formal education.

Bibliography

- Bacigalupo, M., Kampylis, P., Punie, Y. & Van den Brande, G. (2016). EntreComp: The Entrepreneurship Competence Framework. Luxembourg: Publication Office of the European Union; EUR 27939 EN; doi:10.2791/593884

- Blissett, S. & McGrath, R. (1996). The Relationship between Creativity and Interpersonal Problem-Solving Skills in Adults. Journal of Creative Behavior. Volume 30, Number 3, Third Quarter 1996.

- Chamorro-Premuzic, T., Arteche, A., Bremner, A. J., Greven, C., & Furnham, A. (2010). Soft skills in higher education: Importance and improvement ratings as a function of individual differences and academic performance. Educational Psychology, 30(2), 221-241.

- Cinque, M. (2015). Comparative analysis on the state of the art of Soft Skill identification and training in Europe and some Third Countries. In Speech at “Soft Skills and their role in employability–New perspectives in teaching, assessment and certification”, workshop in Bertinoro, FC, Italy.

- Cimatti, B. (2016). Definition, development, assessment of soft skills and their role for the quality of organizations and enterprises. International Journal for quality research, 10(1).

- Cukier, W., Hodson, J. & Omar, A. (2015). “”Soft”” Skills are Hard. A review of the Literature. Ryerson University. Diversity Institute.

- Harari, Y. (2020). How to Survive the 21st Century. World Economic Forum. Davos. Available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gG6WnMb9Fho

- NWEA & Gallup (2018). Assessing Soft Skills: Are We Preparing Students for Successful Futures? A Perceptions Study of Parents, Teachers, and School Administrators. Gallup Inc. Washington DC. USA”

- OECD (2017), Getting Skills Right: Skills for Jobs Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264277878-en

- Wagner, T. (2008). The Global Achievement Gap. Why even our best schools don’t teach the new survival skills our children need and What can we do about it. Basic Books, New York. USA.

- WEF (2021). Building a Common Language for Skills at Work. A Global Taxonomy. January 2021.